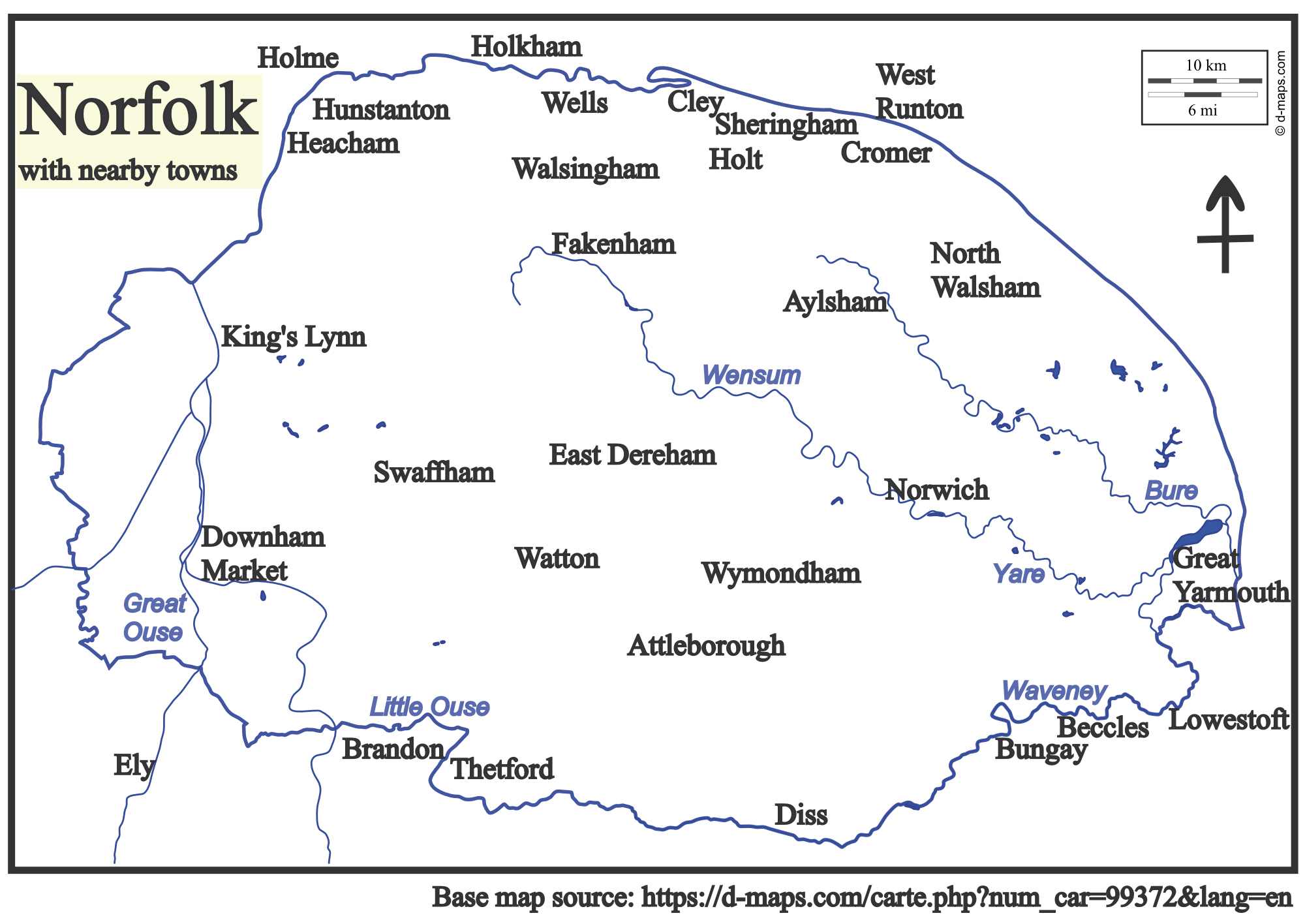

Norfolk is a large county, bounded to the North and East by the North Sea, to the West by the Wash and the Fens, merging into Lincolnshire and Cambridgeshire, and to the South, across the valleys of the Little Ouse and Waveney, by Suffolk. The division of East Anglia into Norfolk and Suffolk is somewhat artificial, coming from the seventh-century ecclesiastical parcelling of the Kingdom of East Anglia into bishoprics that were given a broader meaning during the Danish occupation in the ninth century. Whilst there is a good-natured rivalry between the two counties, they have much in common, and the division along the fairly small rivers of the Little Ouse and Waveney makes little difference in practice, with some areas switching between counties over the years.

Indeed, the ancient British people of the area, the Iceni, had a territory which covered all of Norfolk and perhaps half of Suffolk. Boundaries were not rivers, but the watersheds between them - the higher, drier, less fertile areas where people went less, daily life and economy being focused on the river valleys. Norfolk has a major watershed running in a crescent North to South roughly West of Fakenham and Watton (see the map). West of this, people still look to King's Lynn; East of it they look to Norwich. In the South of the county lies the sandy landscape of Breckland, shared with Suffolk, with its characteristic pine trees and Thetford Forest. Here the chalk is close to the surface, mined until recent times for the flint to which it gives birth. Neolithic flint mines can be visited at Grimes Graves, North of Thetford and Brandon. This was where Albert Leslie Armstrong (1878-1958) 'found' a chalk goddess figurine in the 1930s, having sent his archaeological team home for the day... On one level, this reflected an archaeological desire of the time to find evidence of the then still assumed worship of an ancient Mother Goddess in Britain, of a piece with Thomas Charles Lethbridge's (1901-1971) 'discovery' of a 'goddess' hill figure on Wandlebury Hill, near Cambridge, in 1954. On the other hand, both of these events could be seen as the spirit of the Chalk calling out to receptive minds. Today, we can recognise the Lady of the Chalk and the Lord of the Flint as divine manifestations in this land.

East of Norwich lies Broadland, an area of freshwater marsh, rivers and shallow, man-made Broads (flooded medieval peat-quarries). This liminal landscape is incredibly fertile and fortunately (after much campaigning by Friends of the Earth in the 1980s) is partly protected as a designated landscape similar to a National Park. It is a place where the dark side of nature can feel as close as the light, with winter-geese honking and strange splashings in unseen dykes. Home to many ghostly tales, this watery place is studded with windpumps, some of which can genuinely be called windmills (as they all frequently are), including that at Berney Arms, close to one of the country's remotest railway stations, and perhaps strangest of all, Saint Benet's Abbey, of which very little now remains above ground, save for rumours of dastardly goings-on by the monks and the legend of the Ludham Worm or Dragon... The remains of the eighteenth-century mill are built into the Abbey gatehouse and both the bricks of the mill and stones of the gatehouse have graffiti ranging from Victorian and later mark-leaving to more magical and religious examples from previous centuries, all surmounted by a dragon (or possibly lion) and knight of the same kind as grace Norwich Cathedral's Ethelbert Gate. It all adds to the eerie feeling here.

Outside, a tall wooden cross now marks the original altar and people leave offerings here - it is turning into a coin tree, as people push coins into its cracks - and flowers left provide tidbits (of questionable safety) for the resident cattle. The Abbey sits between three rivers, the Ant, Bure and Thurne, on which a wherry sometimes still sails past. These were the traditional trading vessels of the Broads, superseding the older keels (which had the same basic design as Viking long-ships) in the seventeenth century, before themselves giving way to the railways in the nineteenth. Towards the end, some were converted into pleasure wherries. Some were actually built as pleasure wherries too, including the 'Hathor', which still sails today (thanks to the Wherry Yacht Charter), named after the Egyptian goddess and decked out with Egyptian imagery. She was built in memory of Alan Cozens-Hardy Colman (1867-1897), who had died at Luxor on board a Nile cruiser of the same name, having been commissioned by two of his sisters, Ethel and Helen. She brings some of Hathor's grace, beauty, joy, power and fecundity to this more temperate 'field of reeds', Our Lady of the Broads.

Whilst the trip to Egypt with Alan was a sad time, his father, Jeremiah James Colman (1830-1898, of mustard fame) took the opportunity to acquire many antiquities, and Ethel (1863-1948) and Helen (1866-?) later became enthusiastic members of the Egyptian Society of East Anglia, caring for their father's Egyptian collection after his death and eventually donated it to Norwich Castle Museum, where it forms the core of the Egyptian collection. Hathor must have smiled when Ethel became Norwich’s first female Mayor in 1923, with Helen as Lady Mayoress! Norfolk has other modern connections to ancient Egypt too. Howard Carter (1874-1939), most famous for excavating Tutankhamun's tomb, was brought up in Swaffham, and novelist Sir Heny Rider Haggard (1856-1925) was born in Bradenham and wrote most of his novels in Ditchingham, where he is buried. There is even a couple of pyramids: a tall one, after a Roman original, at Blickling, and a small example in Attleborough Cemetery, marking the grave of Meloncthon William Henry Lombe Brooke (1839-1929), an early 'fringe' Egyptologist.

The North Norfolk Coast is different again, with its shifting sand and silts, shingle ridges and shell-strewn sand, salt marsh and chalk reefs, and Shuck-roamed cliffs. This tranquil holiday realm was once a string of small ports and vibrant fishing communities, some of which remain. The churches at Blakeney and Cley are festooned with medieval ship graffiti - possibly votive offerings for voyages to be taken or safely completed. At Sheringham, a mermaid once ascended the hill to the church in what is now Upper Sheringham, longing to hear the music, but was shut out - although she managed to slip in anyway. Her memory lives on in a bench-end carving near the door.

Further West, at Holkham, where the remains of an Iron Age fort can be glimpsed on the National Nature Reserve, the Anglo-Saxon Saint Withburga started Her miraculous career as a child, with stones gathered from the shore to build a church, before going on later in life to found a nunnery at East Dereham, aided by lactating does sent by Mother Mary (more on whom below).

At the western end of the coast lies the natural splendour of Holme, where two Bronze Age timber rings were uncovered by storms in 1998. One was dubbed 'Seahenge' and resulted in a great deal of controversy, as archaeologists wanted to dig it up and locals and Pagans together wanted it left where it was. The archaeologists got what they wanted (and half of the ring is now displayed rather oddly in King's Lynn Museum), but the second ring remained unremarked and was allowed to retain "a transient beauty" (to quote Libby Purves, writing in The Times of 29th June 1999).

Around the coast, on the Wash shore and on the way to Sandringham and Kings Lynn, lies Heacham. This was the home of the Rolfe family, one of whose number, John (1585–1622), sailed to Virginia with his pregnant wife (whose name is not recorded). En route, their ship was driven aground on Bermuda, in a storm that partly inspired Shakespeare's The Tempest, and their baby was born there, but died after a few days. The shipwrecked survivors built two smaller ships and eventually, in 1610, reached Jamestown, but Mrs Rolfe died shortly afterwards. Three years later, John met and married a young woman who had, as a child, been a symbol of friendship walking in front of people from the Powhatan First Nation bearing food supplies for the English 'visitors', and had later been made hostage by the settlers and given the Christian name of Rebecca. Several names are associated with her, but Rebecca Rolfe is best known as Pocahontas - best known, but for all the wrong reasons, as her story was falsified and used as propaganda even during her short lifetime. Her adult life was decided for her by others, yet she chose a path, not of acquiescence, but of honour. Whilst in England in 1616/7, for what would be the last year of her life, her 21st, she visited Heacham with John and their son, Thomas, an event commemorated on the village sign, along with two equine supporters, one of which is a crab-clawed sea-horse (or merhorse perhaps), reflecting the traditional role of horses in launching fishing boats from the beach. Pocahontas herself could be likened to a mermaid - a being between cultures, between worlds, and a 'fish out of water' in her strange 'new world' that was seventeenth-century England.

Sadly, she became very ill as her ship back to her homeland sailed. Taken ashore at Gravesend, Kent, she died and was buried there on 21st March 1617. Presumably John, having lost a second wife, feared for the young boy on the voyage, and Thomas was left to be brought up by relatives in England, not reaching Virginia until his father was dead too. Five years after her death, the 'Peace of Pocahontas', that had existed since she became a bridge between peoples, collapsed in a bloody rebellion and reprisals, from which the Powhatan First Nation never recovered. The rest, as they say, is history. Legend is a different thing, however, and Pocahontas' story, twisted for propaganda, was used for various dubious causes. But today it has turned, at its best, into something positive: a powerful feminine ‘Noble Savage’, from the apparent wilderness, who shows us something better, at once more innocent, more powerful, and wiser than the dystopia of our own society.

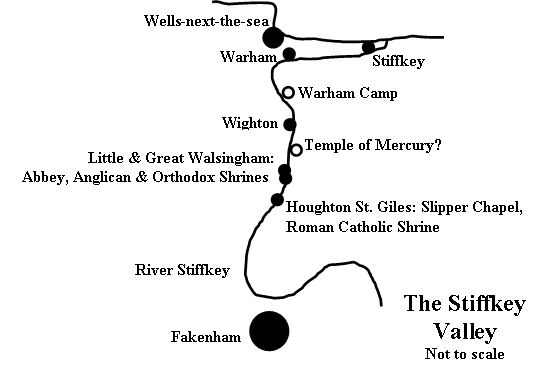

Inland from the north coast, there is a special valley, that of the river Stiffkey. This is a rare chalk valley, of great interest for nature conservation, with an interesting landform history. Until the last, Devensian glaciation, 20,000 years ago, the river flowed out to the sea near what is now Wells-next-the-Sea, but the ice sheet stopped up the valley, creating a lake, which eventually found an exit eastwards, that persisted when the ice melted. Coincidentally, the parish in which the diversion occurs, one of three for the tiny village of Warham, is dedicated to Saint Mary Magdalene, the controversial Mary in the Christian myths - and there is even a local tradition that She is buried here!

Upstream of Warham, there is an Iron Age enclosure, now a haven for chalk grassland plants and animals, known as Warham Camp, and a magical place to visit. Further upstream, above the village of Wighton, there was a Roman settlement, with shrines to several gods, and votive representations of Mercury and Minerva conspicuous. Most famous of all, a little further up the valley, is Walsingham: one of the greatest Christian shrines of the Middle Ages, ‘England’s Nazareth’, sacred to the Annunciation of Saint Mary, Mother of God, whose relic was a chalky vial of Her milk. Today, there are shrines to Mary in Roman Catholic, Anglican and Orthodox traditions, as well as churches of other denominations. Pilgrims of other faiths are drawn here too. A Muslim man from Cairo donated a silver dish to the Anglican shrine in the 1960s. Tamil Hindus accompany their Christian fellows to the Catholic shrine. And Pagans often find they are drawn here too. The gods, and spirits of place, speak to all of us if we are prepared to listen and honour the waters of this sacred place. Today, we can see the Lady of the Chalk, white Mother of this land, with its wide blue sky, speaking through the image of Mary, in Her robes of white for purity and blue for the Queen of Heaven. The iconography of Mary also includes elements of the already existing Queen of Heaven, Isis, as Mary’s cult deliberately adopted them. Through Mary, we can connect to Isis. Or perhaps all three are but faces of something beyond, the symbols by which we and the ineffable attempt to communicate?

Behold the Queen of Heaven rising from the sea, the land cupped in Her hands, Her sacred waters flowing between Her fingers: Isis Unveiled.

Norfolk generally seems a tranquil place today, but it has not always been so. In the Iron Age there were skirmishes between the British tribes and sometimes people would simply up sticks and move - there was a branch of the Parisii in what is now East Yorkshire and a swathe of tribes across England identified as Belgic - but whether that was mass migration, invasion or a more peaceful takeover by an incoming elite is not clear. People went the other way too, with Britons settling in what are now Brittany and Normandy, for instance.

As the Roman Empire grew and expanded its horizons, trade with Britain brought Roman products and culture to these shores, and, by the time the full-blown invasion happened in 43 CE, some rulers in the South welcomed them to (as they thought) stand as allies against local enemies. The Iceni remained aloof until they were 'disarmed' in 47, after which Prasutagus was set up as a 'client king'. He died in 61 and the Romans sought to take over, which led to the Boudican Revolt. It seems those who were left were the more Roman-orientated Iceni and the territory was assimilated as a civitas. A programme of road-building ensured the military could suppress any future rising, of course. Over the next three centuries, the people of the Civitas Icenorum became Roman and Latin seems to have become the lingua franca.

Rome withdrew formally in about 410CE, leaving a Romanised Britannia to its own devices, and defences. There was certainly some settlement by Germanic people, but this was not the wholesale replacement of one people by another as once believed. There was no 'ethnic cleansing'. Indeed, people had been coming from across the North Sea (or the German Ocean, as it used to be known) since the Neolithic, and there is evidence of a Germanic element within the Iceni federation of tribes. It appears that more people came when the Roman occupation ceased, but more importantly Germanic culture and language came to predominate, if with a wistful look back to the 'glories of Rome'. Somehow the Civitas Icenorum seems to have morphed into the Kingdom of East Anglia, with its rulers tracing their lineage back to Woden, via Caesar. Germanic, Celtic and Roman styles are all evident in the famous ship burial at Sutton Hoo. And their symbol was the wolf: they were the 'little wolves' and looked up to Rome and adopted Roman Christianity - both of which had the suckling she-wolf as a symbol.

The skirmishes continued. Only now they were bigger affairs, against larger kingdoms: particularly Mercia and eventually Wessex. And then there were the Danes. Edmund, King of East Anglia, was defeated by the Danish invaders, tortured and beheaded in 869 CE, perhaps in Suffolk, perhaps in Norfolk. The story goes that his head was found by the English, being guarded by a wolf. The Danish invasion led to the annexation of half of England, before being stopped by Alfred, who agreed terms, which led to the establishment of the Danelaw in 886. Wessex fought back, establishing the Kingdom of England in 954, although it became part of the Danish empire again under Cnut. Thereafter, the kings of England were at least related to Northmen, and they took over fully in 1066 with the invasion of the Normans (i.e. northmen).

An Anglo-Saxon nobleman by the name of Hereward held out against the Normans, taking refuge on the Isle of Ely. He is one of the inspirations to the Robin Hood legends. One tale told of Hereward is also told of Robin, that of disguising himself as a potter to get close to the enemy, and the play of Robin Hood and the Potter survived because it was performed and preserved by the Norfolk Paston family.

Norfolk had its own Robin Hood as well. Leaving aside 'John Amend-All' (i.e. Roger Church appropriating a name used by Jack Cade in 1450), who appears to have embarked upon a campaign of looting and highway robbery dressed up as anti-noble justice in 1452, there was Robert Kett.

In the summer of 1549, Kett led a march on Norwich (then England’s second city), which became a major rebellion, calling for justice. The rebels camped outside the city on Mousehold Heath and in Thorpe Woods, developing an alternative commonwealth, but were eventually defeated in a pitched battle by the Earl of Warwick, and Kett himself was executed as a traitor. This call for justice at a time of fractured governance (the King was sickly boy, Edward VI, and the Duke of Norfolk was in the Tower), articulated by 'outlaws' in the woods and wastes outside the city, was instrumental in the development of the first national poor law, as it sparked the levy of a poor rate, which was expanded as part of a fuller system of poor relief in 1570 by John Aldrich, who in turn was asked to model the national scheme at the suggestion of Archbishop Matthew Parker, who had preached in Kett’s camp - and beat a hasty retreat, because he preached against rebellion...

Kett's Rebellion was the second largest popular protest (after the Western Rebellion that spring) of a series of 'campings' across southern England. Ordinary people's ways of life were being squeezed by the dual pressures of the rise of what became known as capitalism and the Reformation. Worse was to come, however. Less than a hundred years later, the whole country was torn apart by the Civil War, with families bitterly split. Norwich declared for Parliament, as did Great Yarmouth, whereas King's Lynn and Lowestoft were Royalist. Relatively little blood was spilled in East Anglia, but it was a fraught time, with tensions still running high even after the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660. This is how Sir Thomas Browne came to be offered his knighthood during Charles II's visit to Norwich in 1671 - he was proposed after Norwich's Mayor, a Parliamentarian, refused the honour.

Browne perhaps epitomised the different tensions that were evident after the Civil War: the changing intellectual environment that became known, not entirely accurately, as the Enlightenment. Browne today is a figure seen in dramatically different ways: as a proto-scientist or as a mystical alchemist. Actually, like Sir Isaac Newton, he was both. He espoused a “dual reality”, allowing religion and natural philosophy their respective domains of truth. He was a true Renaissance philosopher, before the division of reductionist science from broader natural philosophy, and before chemistry was refined from alchemy. He was a friend of John Dee's son, Arthur, who had retired to Norwich, and who bequeathed Browne his alchemical papers. But there is one event that everyone finds difficult to understand about Browne: his testimony as an 'expert witness' in the trial for witchcraft of two Lowestoft women, Amy Denny and Rose Cullender, in 1662. The case, before the assize court in Bury St. Edmunds, was later used as a precedent at the Salem witch trials. Whilst he testified as a doctor that the reported symptoms of the allegedly bewitched could be explained by natural causes, he also said that it would be typical of the Devil to make evil look like natural causes. He went on, gratuitously it appears, to relate a case from Denmark that had similarities. Clearly, Browne kept his head down on controversial matters, like King and Parliament (having been a Royalist in a Parliamentarian city), and would not challenge anything that was considered part and parcel of Anglican faith, like the existence of malevolent witches, whilst going to obsessive lengths to prove or disprove inconsequential things. Of course, Browne had seen how families were torn apart by the Civil War, and he had studied in Padua just 32 years after the judicial torture and murder of Giordano Bruno (whose name, Browne may perhaps have felt, brought things uncomfortably close to home). But then he was himself party to the judicial murder of Amy Denny and Rose Cullender…

Subsequent wars (until the 20th century) were fought beyond these shores - the wars of Empire and colonialism. Norfolk played its part in those phenomena too. King's Lynn is associated with such people as George Vancouver and John Smith, Heacham with John Rolfe, and Great Yarmouth was a port of embarkation for the NW Coast of America. Norfolk was also the birthplace of Horatio Nelson. The county changed dramatically, however, due to the industrial and agricultural revolutions of the 18th century.

Despite the image of Norfolk as an untouched agricultural back-water, industry has actually made a significant mark on the county. As well as the well-known major industries, such as shoes, fishing, textiles, food processing and agricultural equipment, signs of small-scale industry can be found in its most rural corners. Some of the mills of the Broads were actually that: St. Benet's Abbey mill produced lamp oil from colza seed (similar to rape seed) and that at Berney Arms ground cement. The broads themselves are flooded peat workings. Boatbuilding was once widespread in the Broads, as was brickmaking. Even today, the processing of sugar beet is obvious at Cantley, on the Yare. Mousehold Heath is literally pockmarked by mineral extraction and processing, and the Norwich valley-sides show the old chalk, flint, sand and gravel quarries clearly. Mills once lined the hillside overloooking Norwich.Ironfounding was widespread, and signs of its products can still be seen, such as access hole covers and bridges. The Boulton and Paul factory in Norwich pioneered chicken wire and built aeroplanes and airship components. In 1918, an extension to the Norwich tramway was built from Gurney Road to the Mousehold aerodrome to carry planes from the Riverside factory for testing. But ironworking in Norfolk goes back a long way, and evidence of Medieval iron extraction and smelting can still be seen on the Cromer Ridge, using the resource of sandy iron nodules that can still be found in the soil of the boulder clay plateau of NE Norfolk and falling out of North Norfolk's cliffs. In recent years, as well as modern industries, from bioscience to wind-power, some of the traditional industries have returned, at various scales, including brewing, distilling, art and craft textiles, ceramics and metalworking.

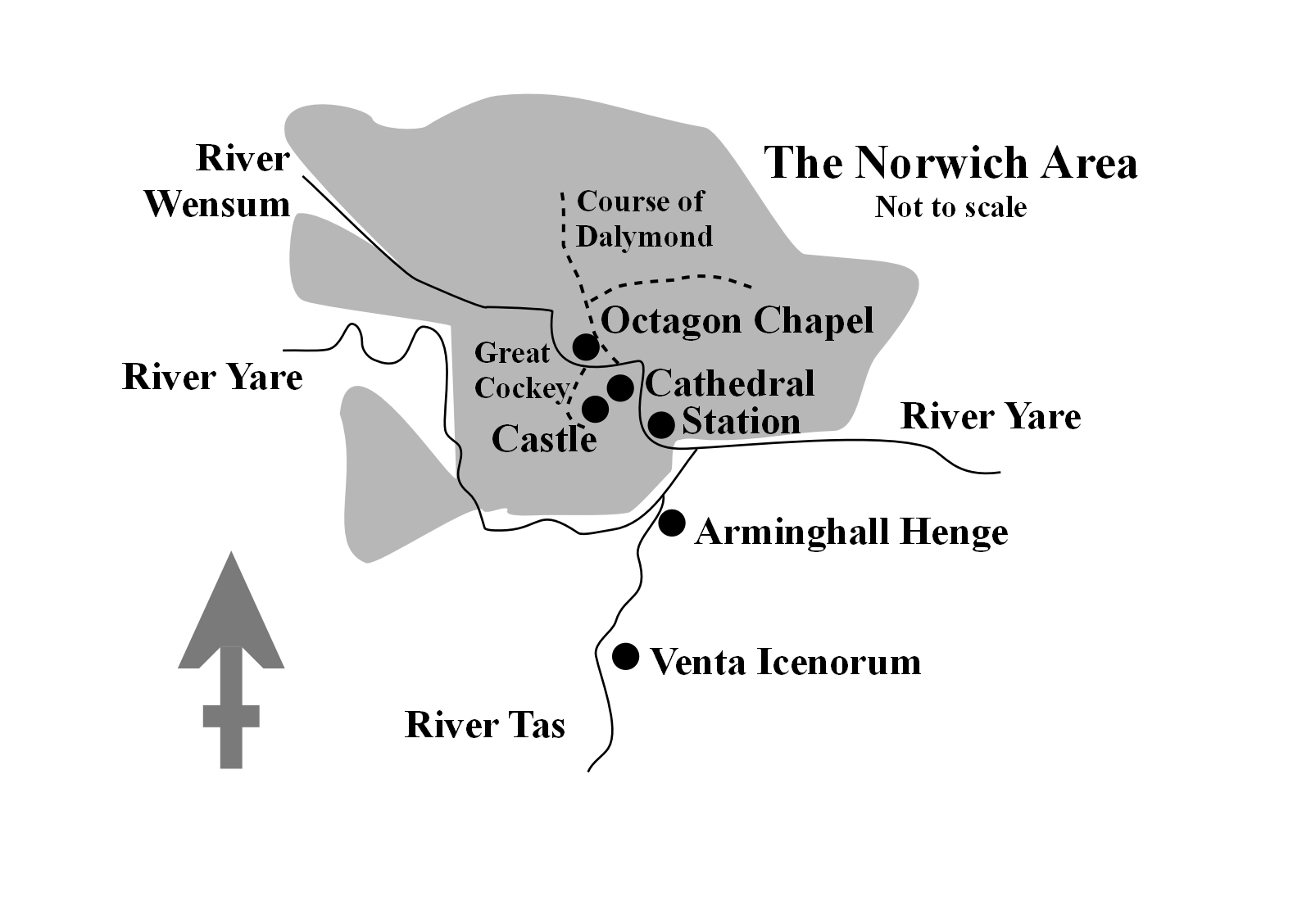

There is evidence for the occupation of the Norwich area since at least the Neolithic. The Yare and Tas valleys were clearly seen as a sacred landscape, with Bronze-Age barrows and at least three henge monuments, and a number of Iron-Age enclosures. The best known of the henges is at Arminghall, between the suburbanised villages of Trowse Newton and Old Lakenham. The bank is still visible and it is accessible, next to a footpath in a field under grazing. The henge is in a typical location, just above a river, but is also hemmed in by an electricity sub-station, a busy road and a railway, and straddled by high-voltage power lines. The timber circle which once stood here appears to have been aligned with the view of the Midwinter Sun setting as if rolling down the side of nearby Chapel Hill, now cut through by a railway and the view itself slighted. But more of this later!

In the Romano-British era, the main settlement in the area was on the river Tas, at Venta Icenorum, latterly fortified with walls that make a startling herald of the City of Stories as the train from London nears its destination. The Roman town contained a forum, baths, amphitheatre and temples, and now hosts the parish church of the village of Caistor St. Edmund. A major Anglo-Saxon cemetery lies nearby.

It appears that a Roman road ran from Venta to a point east of the confluence of the rivers Yare and Wensum, opposite a potential quay and the end of a road that ran south from Brampton. There is also evidence of a routeway roughly following Dereham Road, St. Benedict's, St. Andrew's, Princes Street, Bishopgate and Gas Hill. In the Anglo-Saxon era, Venta declined and small settlements in the curve of the Wensum grew up, most importantly Northwic, with a quayside around modern Fishergate and a ford that became Fye Bridge. It was the coming of the Danes, however, that spurred the growth of Norwich as a cosmopolitan trading city. The legacy remains, in the preponderance of streets called 'gate' and in the original marketplace of Tombland ('tom' = empty). But it was the descendants of other Vikings that gave Norwich the shape we see today: the Normans.

Norman rule changed the Anglo-Scandinavian town, clearing large areas to make way for the marketplace, castle and the Cathedral with its close. A prosperous city emerged from this disruptive make-over, becoming the second city in England, but one with tensions which sometimes ran high. The Normans had brought a Jewish community with them as financiers (Christians not being allowed to lend money at interest, but happy to let Jews do this for them), but this special relationship died as anti-semitism grew. Norwich was witness to mass-murder of Jews in 1190, the synagogue was burned down in 1286 and all who would not convert to Christianity were expelled from England in 1286, their property confiscated. The Church was not immune to violence either. The relationship between the Cathedral and city folk was fraught from the 13th to 15th centuries, with riots in Tombland in 1272 and 1443, in the first of which the Cathedral sustained major fire damage. Things settled down in the 1520s, just in time for the Reformation to shake everything up, Kett's Rebellion to turn the city into a war zone in 1549, and the burning of 'heretics' to take off and make Lollard's Pit "a place of popular entertainment" (to use Trevor Nuthall's term: Norfolk Archaeology, XLVI part III, 2012, pp. 387-393). Following the Civil War, the Restoration and the beginnings of toleration for non-Anglicans in the Act of Toleration of 1688 (not even extended to Unitarians and Catholics until 1813 and 1829 respectively, and, whilst Jews had been readmitted from 1656, other faiths had longer to wait...), sectarian violence began to decline in a Norwich that became rather more welcoming in the modern era. Indeed, when the 19th-century synagogue was destroyed in an air raid in 1942, local churches rallied round and offered the Jewish community places for worship; the Spiritualist Church on Chapelfield North hosted the Norwich Hebrew Congregation until 1948.

Norwich stayed largely within its 14th-century walls until the early 19th, when urbanisation and industrialisation led to population growth. Fortunately, large remnants of open space remain, particularly what is left of Mousehold Heath. The Wensum valley sides were built upon, with gaps where the ground was too steep or unstable due to the earlier quarrying. As recently as 1962, major building plans had to change due to the discovery of chalk workings: the old terraces between Ber Street and Rouen Road were to be replaced by three tower blocks (like Normandie Tower) until voids were discovered. With some reticence, the City Council brought in a dowser (Bill Youngs) to locate the mine tunnels, the City's embarrassment not being abated by the fact that his findings were proved correct by excavation! The tower blocks were built in Heartsease instead.

Norwich has always been about its rivers and its valleys. Some of Norwich's watercourses are the major, living rivers that have allowed it to be the city that it is: the winding Wensum, cut deep into the chalk bedrock, at the city’s heart; the Yare, forming the southern boundary, which gathers up the Wensum before meandering off into the Broads; the Tas, once navigable up to the Roman city of Venta Icenorum, which also adds its flow to that of the Yare.

The city has had more rivers than this, though, and some of them still flow in the groundwater and have left their legacy above ground too. The Great Cockey ran through the Medieval city from the South, but was ‘superseded’ by modern drains and sewers. Artistic paving now commemorates it on Westlegate. From the North came the Dalymond, with its tributary from the heights of Mousehold Heath to the North-East. They are still evident as significant groundwater flows and show up on flood risk maps. Their valleys are still discernible as one walks around ‘North City’ with a curious eye. And here was Dussindale, the scene of the final battle of Kett’s Rebellion in 1549.

We are newcomers to the rivers, yet they have shaped our lives and our cities. Rivers are living beings of the landscape and not simply in terms of their role as ecosystems. Just as we emerge from the collective soul-stuff of the Universe for a time, to flow through a life of consciousness, before descending once more into the ocean of the Underworld, so too do rivers emerge from the common groundwater and flow across the surface of the land for a time, some, like wadis, for just a season, others for far longer than humans have existed. Like us, rivers shape the world around them. They create valleys that are followed by future flows of water, just as we leave behind structures, families, stories and ideas that guide the lives of future generations. Rivers are our ancestors too. We have no records of our forebears honouring Norfolk's rivers as deities, but rivers have been honoured in this way elsewhere, and indeed worldwide. And they still are.

In Norwich we have two polar forces: the Lion and the Dragon. The Lion started as the medieval symbol of royal power in the Castle Fee, surrounded by wyverns, but after 1345, it followed the restoration of the Castle area to the City and became the symbol of the City. The Lion, in its look-at-me mercantile pomp, can be seen as defender, like the sword-holding example at the Red Lion pub, keeping watch over Bishop Bridge. The wyverns transformed into the Dragon that weathered the storms of religious change to come down to us as the processional Snap, the regular feature of Camra Beer Festival logos, and the face gazing down from modern murals, antique spandrels and ecclesiastical carvings. The controlling corporate Lion sits contentedly at the heart of the City, whilst the Dragon’s wild, anarchic energy swirls around, bringing the City its prosperity and cultural vigour.

Centres of sacred power move around. Sometimes they are the same places, of course, whether or not the spirit of the land is acknowledged, or suppressed beneath an on-lay of exotic or simply exoteric religion. But like grass growing through the pavement, the spirit of the land (or indeed of other lands carried like seeds with the exotic cults) emerges where it can, sometimes facilitated by more sympathetic creeds.

One interesting offshoot of Christianity is the Unitarian Church, whose Norwich congregation has left its mark on history. One of its number, William Smith, MP for Norwich from 1802 to 1830, succeeded in getting an Act of Parliament passed in 1813 that permitted non-Trinitarian beliefs and the legal use of the name ‘Unitarian’. He was also instrumental in the repeal of laws limiting public office to Church of England communicants (in 1828). The congregation reflects the pluralism of today’s Unitarian community, from devout, but non-Trinitarian Christians to Atheists, and includes several Pagans. The Norwich Unitarians meet in a wonderful, mid-18th-century building by Thomas Ivory, called the Octagon Chapel, because of its shape.

Being an octagon, the building is supported by eight tree-like pillars in a circle. Church pillars, as with other aspects of ecclesiastical architecture, owe a great deal to those of the temples of ancient Rome, Greece and Egypt. These in turn represented originals from the plant kingdom, huge trees or papyrus stems from primordial sacred groves. This ring of eight 'trees' has a local resonance with Arminghall Henge, two miles to the South, which in its heyday enclosed eight huge wooden posts, arranged in a (horseshoe) ring. The Octagon Chapel is in the heart of the thriving business hub of Norwich, but looks beyond the imperatives of trade, in a place accessible to everyone. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the Godly Protestant merchants dominated Norwich, providing most of its mayors, for instance. The Non-Conformist radicals emerged from this period like mammals from the age of dinosaurs, living in the place of business, using its infrastructure, indeed doing well by it, but not being bound by it. Most of Norwich’s ‘great and good’ of the 19th century were Non-Conformists of one kind or another, and many were significant philanthropists and reformers.

By the beginning of the 21st century, the numbers of Pagans had become significant in and around Norwich, as elsewhere, and Paganism is increasingly open. The range of beliefs within Paganism is probably as diverse as that within Unitarianism. But sometimes we Pagans can hold onto tokens of the ancient past with too narrow a focus. Sometimes we reject the city and look to the countryside, even if that countryside is surrounded by the detritus of the modern industrial world (as at Arminghall), so long as there is a relic of the ancient world to be found. Whilst the natural world is ideal, the city is where many of us live and work (in mundane, spiritual and magical senses) and is a more appropriate place to be than peripheral sites where the ancient honouring of the land has turned sour. Just like the Octagon Unitarians, with their diverse beliefs in their architectural gem of a grove, we can be in the heart of the city and look beyond it.

You can also watch Witchcraft in the Landscape with Val Thomas on YouTube!

Page written and © by Chris Wood.